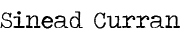

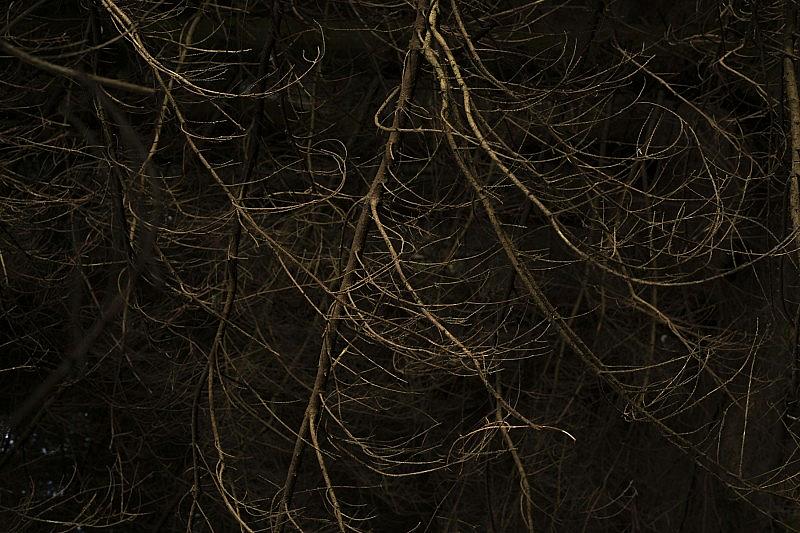

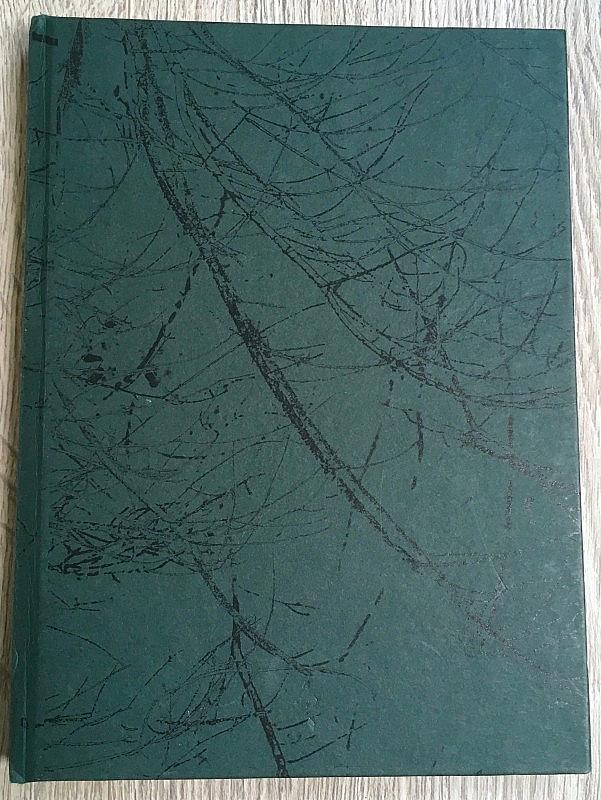

First Plantation (2019)First Plantation is a body of work comprises of photography, video and installation that examines the lifecycle of a forest plantation to maturation, an ontological idealism, and the way people observe and relate to the forest landscape. It brings to light a series of landscape images taken in the early 1990s by the artist’s father, over a six year period. The landscape was revisited for this project 35 years later, with construction taking place, and coniferous tree felling, both metaphors for a childhood narrative from one of displacement: now a space of uncertainty and disillusionment. The Picea sitchensis or sitka spruce, a conifer introduced from Canada to Irish forestry in 1907 by Augustine Henry, primarily for its commercial benefit. Henry has been a major contributor to modern Irish forestry. Since the early 1900s and even the early 1990s the rate of climate change has accelerated, the non-native Sitka is examines in this work, addressing a human relationship with landscape over many decades. SELECTION OF POEMS Invade In the quiet morning forest, I walked ______________________________________________________________________ Stones The cold wind blew, no roof as we drove ______________________________________________________________________ Sue Rainsford | Little Doors In the early 1980s, drought across Transvaal saw kudu dying of starvation in numbers unprecedented for this typically resistant species. Stranger still, when the recovered bodies were opened it became clear that, although they had indeed died of malnourishment, their bellies and digestive tracts showed ample evidence of food. Slowly, a causal chain revealed itself. Prevented from their habitual wandering and grazing by the dry weather, the kudu had been forced to focus on a select gathering of bushveld trees. This vegetation, realising itself at risk of obliteration, found a way to protect itself. Essentially, it began to produce a chemical that was ‘effectively “tanning” the kudu’s insides, turning off the microbes that encourage normal digestion.’ Despite their previously happy coexistence, once the bushveld trees recognised these herbivores as a threat, they were promptly neutralised. The wood doesn’t care if you live or die. The works in Spruce unfold in the moments preceding such perfectly executed repercussions. In this way, though they are often marked by stillness, they are far from inactive. Their tenor is that of a last, latent lull—a prolonged pause inside of which we might involve ourselves differently with our compromised environment, and perhaps change our fate. Within this interlude the exhibition poses, the notion of dwelling as invoked by Heidegger recurs: dwelling is not a sole issue of shelter, but a matter of our very existence on the planet, and the extent to which that presence proves nurturing. Initially, then, the exhibition seems to ask; What does it mean to dwell? Rather than admonish human activity or aggrandize Nature, the works objectively limn the material ways in which the two coincide. In these photographs, where trees turn to felled trunks which then become planks of wood, and the remaining stumps—their lateral growth now halted—read as an amputation, the Sitka spruce hums quietly; a loaded presence. The very fact of its being in Ireland at all speaks to its initial commercial passage from Canada in 1907, and the intangible trail that passage left behind. Such moments and gestures, as understated as they are charged, speak to the full spectrum of human impact on the natural world; A bridge calls into existence the banks on either side of a river. And so, the question becomes; What does it mean to dwell, given the toll our dwelling has already taken? Spruce suggests a degree of displacement which gradually heightens into disembodiment will be inevitable. Indeed, these works conjures what Daisy Hildyard has termed ‘the second body’, namely a counterpart to our physical, animal self that we gain by being ‘embedded in a worldwide network of ecosystems.’ This second body status, ‘determined by its consumption and emissions’, collapses any ‘meaningful difference between your body and a cow or even a car.’ In Spruce, what we are presented with feels akin to this collapsing of distinction and the altered embodiment such a shift entails. As such, these images present a space in which our agency has been considerably reduced, and our experience is now confined to the slow burning effects of our species’ previous actions. Where did the bread go? thinking we were too much home • In 1874, the chemical compound DDT was first synthesized, and since then this crystalline substance has enjoyed a volatile history; spread far and wide in treating issues symptomatic of overpopulation, it was later infamously condemned by Rachel Carson in her seminal Silent Spring. Carson argued that while this colourless, tasteless and almost odourless chemical was being used to combat malaria and typhus, it was also secreting a very permanent and toxic residue absorbed by mammal and mineral alike. As Gregory Bateson writes In Steps Toward an Ecology of Mind, ‘we still don’t know if the human species will survive the DDT currently in circulation’, and it has in fact been uncovered in human bodily tissue these eight decades later, its presence connected to Alzheimer’s disease. How might we interpret such a lingering aftermath, given the fate of Transvaal’s hungry, thirsty kudu? The images in this exhibition suggest we are witnessing, at least in part, a world where our decision-making power has been largely revoked. Now, we must consider at protracted length the impact of the agency we were once afforded, and ask Given the toll our dwelling has taken, how—if at all—do we go on dwelling? About those things I took: inside you. • ______________________________________________________________________ |